That Familiar Feeling: How to Use Fear to Your Advantage

by Aaron Burrick

As a clinical social worker, I hear it all the time: I can’t do it, I’m too afraid. It’s a statement that comes from grown adults and young children, accomplished ultra-marathon runners and first-time 5Kers. Familiar feelings of worry, stress, and anxiety settle in, and they paralyze us from achieving our goals. But what if there was a way to change our relationship with fear? What if there was a way to reframe how we think about the pits in our stomachs, the knots in our throats? What if fear could be an indicator of growth instead of failure, connection instead of concern? By understanding the relationship between our thoughts and feelings, shifting to a growth-based mindset from a fixed mindset, and asserting our sense of belonging we can learn to use fear to our advantage.

All emotions, including fear, first arise as bodily sensations. The wobble in your legs. The tight shoulders almost level with your ears. The urgent need to use the bathroom, which conveniently arises only moments before the pre-race briefing. The brain perceives these sensations based on prior experience and learning, and labels them as a specific emotion. That’s fear, we think. That’s excitement. That’s terror. That’s boundless, indescribable joy. All of these feelings begin in the body, but come to life in the mind.

Fear is nothing more than a label. A name tag that the brain slaps onto a collection of physical experiences. Personally, these experiences include mile-a-minute conversation, all sorts of stomach issues, and a few facial tics that have come and gone throughout my life. It’s easy to label these feelings as obvious indicators of fear or anxiety, but it doesn’t have to be that way. I can use a different name tag. If I can pause and observe how I’m feeling, I can reframe fearful sensations as signs of opportunity, chance, and discovery. Instead of (literally) running with the labels I automatically assign to my physiology I can turn fear into a force that doesn’t slow me down, but pushes me forward.

When I talk to my students and clients about mindset, I read them this informative but slightly irritating book about Bubblegum Brain and Brick Brain. Bubblegum Brain is up for anything; instead of becoming frustrated when he can’t ride a unicycle or play the accordion, he emphasizes that he just can’t ride or play yet. For Bubblegum Brain, fear exists along the border of possible and impossible, the liminal space where learning happens. And when this learning happens, his brain (and globby, gummy, animated head) can stretch to accommodate these new experiences.

Brick Brain is more of a pessimist. He sees the world in the black and white realms of can and cannot, and fear is the feeling that pushes him toward the latter. He whines and complains his way through the book, but only until arriving at what my students describe as “the twist.” Brick Brain’s head wasn’t a brick at all, it was a bubble gum wrapper. On the last page of the story, Brick Brain unwraps his papery epidermis to reveal the same globby and pink interior as Bubblegum Brain. He’s capable of shifting from not to not yet, from fear to possibility.

When I read this story, I’m struck by the reality portrayed in these two characters. In the greatest confessional to ever come from a children’s book: I’ve been Brick Brain before. I’ve looked at vert profiles, workout descriptions, and the long-legged attendees of run clubs with a fixed, brick-like outlook. No way can I complete this course, I’ve told myself, no way can I hit those splits on another cold, rainy, Northwest evening. No way can I keep up with these guys. But then I think about Bubblegum Brain. I think about the strength gained by hills and hard workouts, the friendships and conversation developed on a group run. I think about everything running has already given me, and everything I’ve yet to learn. I cross from fear to curiosity, and I enter into a mindset where anything is possible.

Within the study of human emotion, it’s understood that almost all positive feelings involve approaching and connecting to our surroundings. We share our happiness with family members. We’re excited by a friend’s success. Negative emotions, in contrast, involve retreat and isolation. Anger prioritizes self-protection over the needs of others. Fear makes us shy away, hiding within ourselves to avoid expected negativity and disappointment. As runners, we’ve all experienced this type of retreat: bailing on an early run or late-season race, questioning a weekend adventure, doubting the capabilities of our joints, muscles, and bodies.

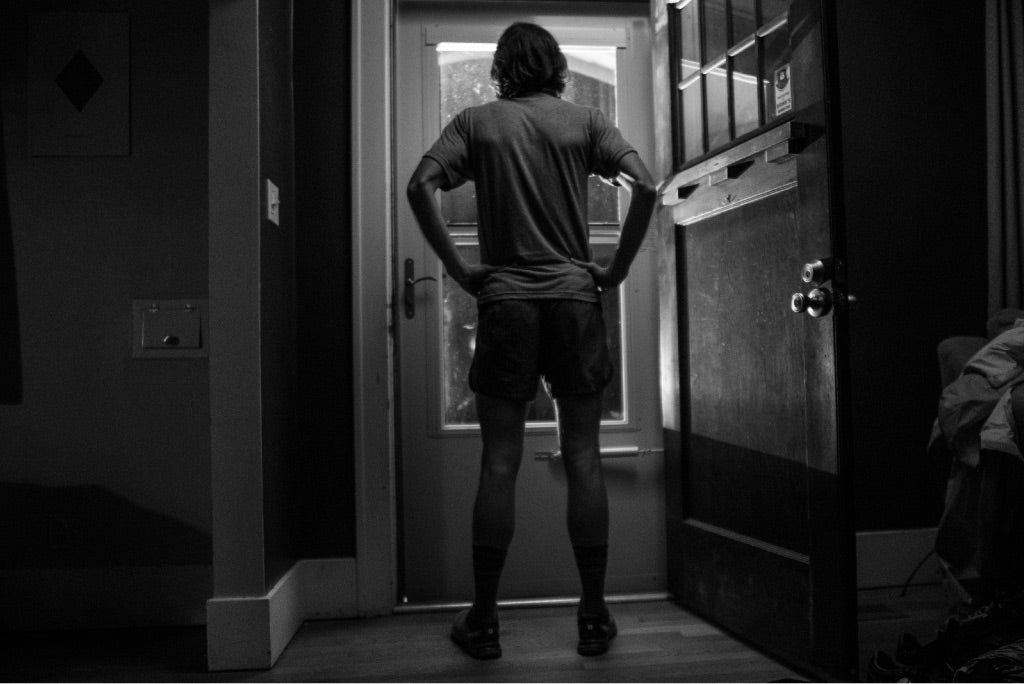

When faced with feelings that tell me to hide, it’s more important than ever to assert my belonging. To proudly align myself as a member of the trail running community, a group of people that always seems to see my abilities before I notice them myself. To stake my claim under the evergreen canopy of the Pacific Northwest. To see fear not as a reason to run away, but as a reason to run toward. There is so much positivity in these trees, I remind myself, so much strength and beauty and reason to thrive. By asserting our belonging to the trail running community, we can shift from the isolation of fear to the connection of positivity.

As runners, friends, partners, workers, and community members, it’s unlikely that we’ll ever escape familiar feelings of worry, doubt, and anxiety. But if we can assign more positive labels to fearful experiences, shift from a fixed to a growth-based mindset, and assert our belonging within this sport, we can reframe our understanding of fear. Instead of turning away, we can use fear to move closer to our goals, to those aspirations that maybe we just can’t do yet. We can use fear to deepen our relationships to both ourselves and others. We can use fear as fuel, as an energy, as the force that sends us across the start line and toward whatever rests along the foggy trails beyond.

2 comments

fantastic article! thanks for sharing, I know I struggle with the doubt and fear most days! Thoughts: I havent ran that far in a few weeks/months. Thinking Im all the sudden incapable of doing what I know I can. Some days it drives me to overcome the fear others it creeps in and takes over control! Thanks so much

happy trails

The perfect thing to read on a cold January morning! Well done.